Eads Bridge at 150 exhibit at the Missouri History Museum examines the complexities of the bridge’s design, its construction, and the important role it has played since it opened in 1874.

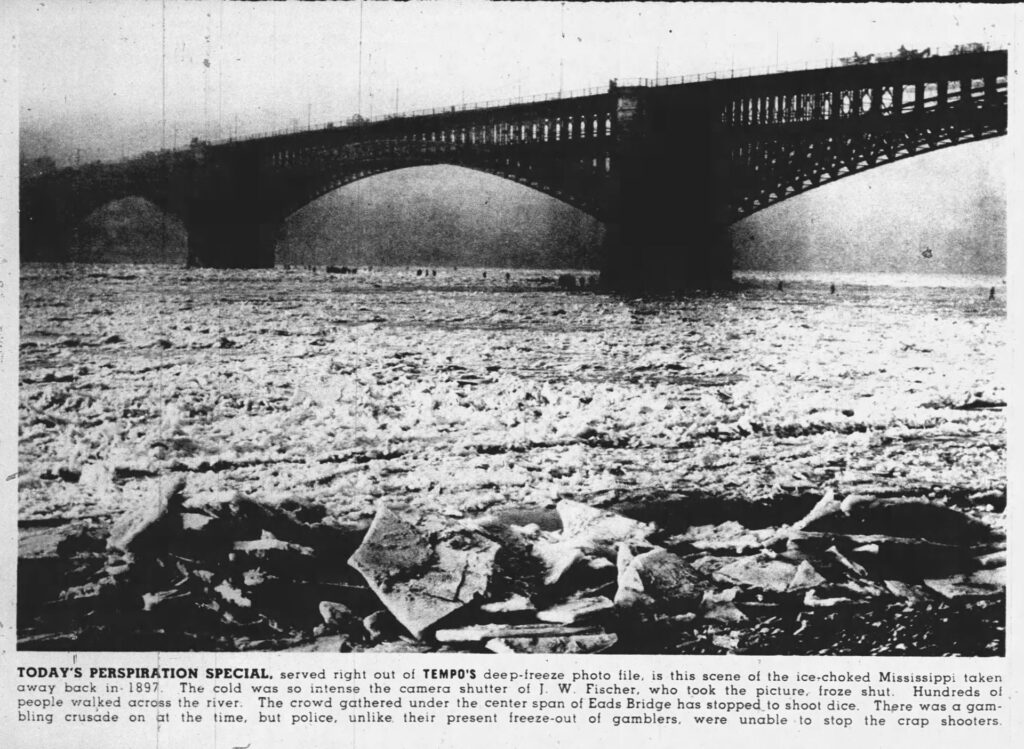

ST. LOUIS, MO (June 21 2024) – As a child traveling to St. Louis for the first time, James B. Eads and his family lost everything as their steamship caught fire and sank to the bottom of the Mississippi River. 150 years after the completion of his crowning achievement, the Eads Bridge endures. Its a symbol of ingenuity standing strong over an unrelenting river that had once taken everything from its creator.

As St. Louis prepares to celebrate a monumental milestone, the iconic Eads Bridge emerges as a testament to human ingenuity and resilience, marking its 150th anniversary this 4th of July. From its humble origins to its enduring legacy as a symbol of engineering marvel, the Eads Bridge stands tall over the Mississippi River, embodying the spirit of innovation that defines the heart of St. Louis.

In commemoration of this historic occasion, the Missouri History Museum unveils the ‘Eads Bridge at 150’ exhibit, inviting visitors to delve into the intricate complexities of its design, the daring construction process, and the profound impact it has had on the city since its completion in 1874.

Table of Contents

ToggleAn Engineering Feat:

A bridge of its magnitude had never been constructed using so much steel—certainly not one with three 500-foot spans. Eads also had to engineer a way to sink the bridge’s foundation. Which had to reach bedrock 100 feet beneath the river’s surface. His innovative design plans—with calculations checked by Washington University’s second chancellor, William Chauvenet, one of the most respected mathematicians in the country at the time—were unveiled in July 1867. Construction took seven years, cost $6.5 million, and claimed the lives of 16 men.

A Designer Who Had Never Built a Bridge:

Eads was a self-taught engineer, first making a career by designing and operating a salvage boat with a diving bell. This bell allowed him to scour the riverbed for steamboat wrecks. After more than 500 trips to the bottom of the Mississippi, Eads retired from salvage work as a wealthy man. In the early 1860s however, Eads won a government contract to build ironclad gunboats for the Civil War. He also invented a steam-powered rotating gun turret for good measure. Though he was well known for his mechanical design projects, Eads had never designed a bridge. Nevertheless, when the Illinois and St. Louis Bridge Company was selected to build a bridge to connect Missouri and Illinois, Eads was named chief engineer of the project.

Bridge Led to Other Scientific Discoveries:

Numerous workers who operated in the Eads Bridge caissons suffered from “caisson disease” (a.k.a “the bends” or decompression sickness). Once on the river bottom, the pressure inside the caisson was more than 40 pounds per square inch. Eads directed his family doctor, Alphonse Jaminet, to build a floating hospital beside the pier and study what was happening. Ultimately, decompression sickness affected 119 Eads Bridge workers and killed 14. Sadly, Dr. Jaminet was unable to completely solve the medical puzzle of caisson’s disease. At the very least, he did realize that gradual decompression was vital. His studies laid some of the foundations for modern diving practices.

Opening Day Safety Stunts Included an Elephant and 14 Trains to Prove Stability:

The opening day celebration of the Eads Bridge was a spectacle, including a circus elephant marching across the bridge to prove its sturdiness, as well as 200,000 spectators, fireworks, and celebrities. 14 trains filled with coal and water moved down its railroad tracks to demonstrate the capacity of the bridge, while a train full of dignitaries were briefly stuck in the tunnel, slowly being overcome by exhaust smoke because the ventilation systems weren’t completed yet (everyone escaped unharmed). After completion, artists came from around the world to capture the beauty of the engineering marvel, including Frank B. Nuderscher, the “dean of St. Louis artists,”

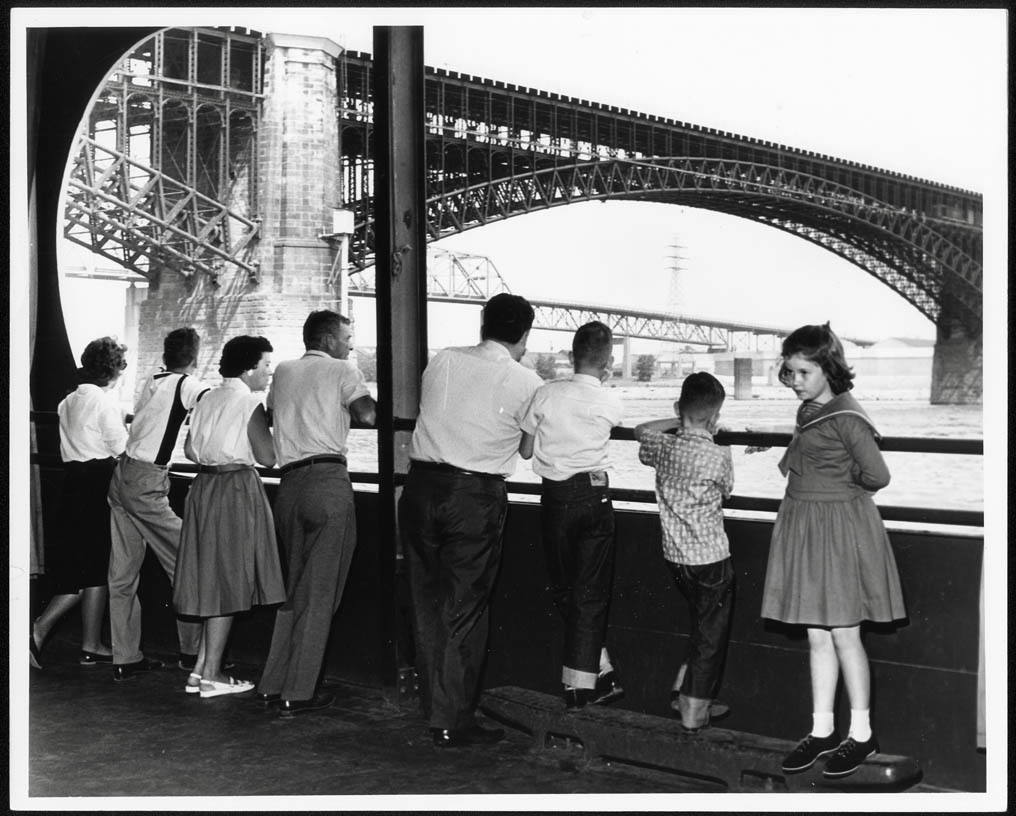

St. Louis’ Original Iconic Landmark:

The Eads Bridge was named a National Historic Landmark, the highest designation given by the National Park Service, in 1964. It was made a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Civil Engineers in 1971 and designated a City Landmark the same year. The bridge is now part of Gateway Arch National Park. Not to mention that it still carries over 2,000 cars and 300 Metrolink trains per day.

Amanda Clark, Community Tours Manager at Missouri Historical Society, calls James Eads and the Eads Bridge the “great loves of her life.” She explains, “I’ve been fascinated by them both for over a decade. The sheer ingenuity, political drama, and the deadly danger faced by its builders make it such a compelling part of St. Louis history. This new exhibit at the Missouri History Museum details their legacy. And its going to make everyone else fall in love with them, too.”

The new exhibit at the Missouri History Museum, Eads Bridge at 150, tells the story of Eads’ engineering masterpiece that became the world’s first steel-arch bridge and St. Louis’ most iconic landmark before the Arch.

How to Celebrate the Anniversary:

The atrium exhibit at the Missouri History Museum is open Tuesday, Wednesday, Friday, Saturday, and Sunday. The hours on these days are from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. The atrium opens 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. on Thursday, but closes on Monday.

Celebrate St Louis (formerly Fair St. Louis) will commemorate the 150th anniversary of the Eads Bridge on July 4, 2024.

Artists are encouraged to visit the bridge and capture its beauty, sharing online using the hashtag #EadsBridge150; the Missouri Historical Society will share some works online.

For more information visit www.mohistory.org.

About the Missouri Historical Society:

The Missouri Historical Society (MHS) has been active in the St. Louis community since 1866. Today it serves as the confluence of historical perspectives and contemporary issues. MHS operates the Missouri History Museum, Library & Research Center, and Soldiers Memorial Military Museum. St. Louis City and County taxpayers fund MHS through the Metropolitan Zoological Park and Museum District (ZMD) and by private donations.